LOUDREADERS

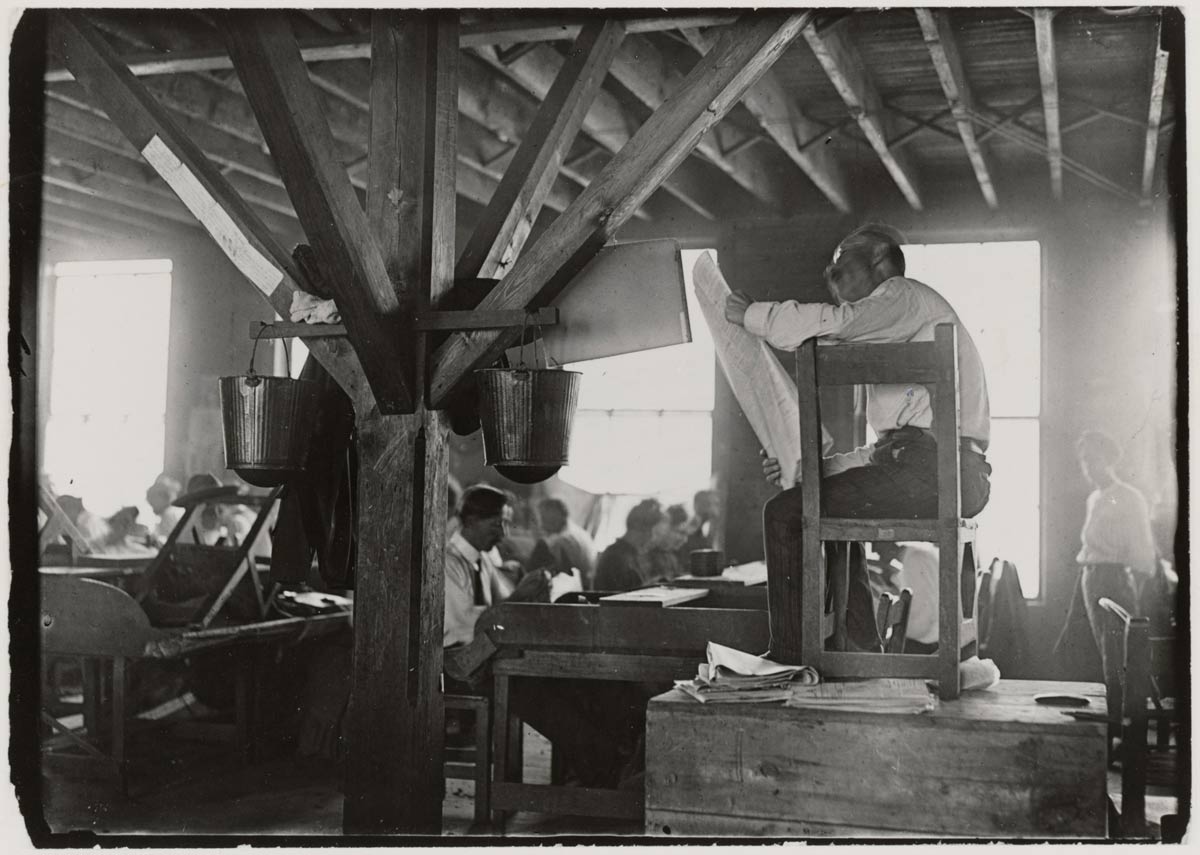

Left: Loudreader reads from the newspaper

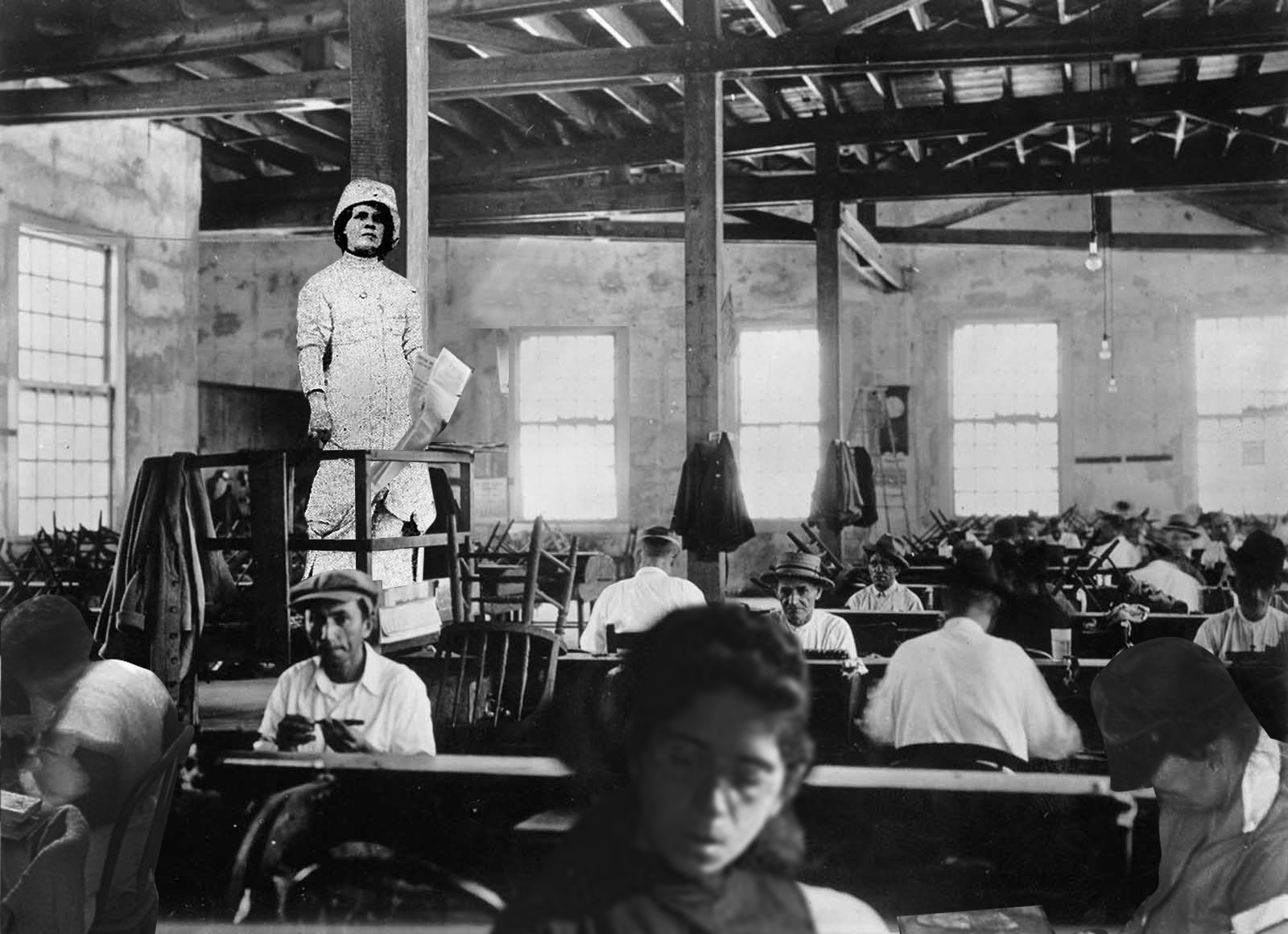

Below: Luisa Capetillo Loudreads in a tobacco factory

![]()

A century ago, at the same

time that the celebrated Bauhaus, under the direction of Walter Gropius, kept

women away from the main disciplines of architecture, sculpture, and painting, in

the US colony of Puerto Rico, a group of tobacco workers, organized in

anarchist syndicates, created a simple and fascinating alternative practice of

education. That practice grew international networks like tentacles over the

map of the Americas, from San Juan to New York, from Ybor City and Durham to La

Habana and Santo Domingo, giving birth to what some historians call the most

enlightened proletariat force in the continent.

The practice was simple. While tobacco workers engaged in the alienating labor of rolling cigars, they would hire one of their own to read aloud for them during the entire work-day. While the readings consisted mostly of newspapers, magazines, and literature, the Loudreaders focused on Darwin, Bakunin, Kropotkin, Marx, and Engels fomenting an anti-capitalist, decolonial imagination. As the practice of loud-reading grew, the lectores (Loudreaders) will become traveling performers with an international audience, creating new networks of solidarity all around the Caribbean as well as a massive, shared, and open access oral library to workers who were denied any other form of formal education. The tobacco workers turned the mind-numbing characteristics of their repetitive, manual, and boring work of rolling cigars into an advantage, using the same space and tools of their capitalist exploitation to create an anti-capitalist underground culture.

The practice was simple. While tobacco workers engaged in the alienating labor of rolling cigars, they would hire one of their own to read aloud for them during the entire work-day. While the readings consisted mostly of newspapers, magazines, and literature, the Loudreaders focused on Darwin, Bakunin, Kropotkin, Marx, and Engels fomenting an anti-capitalist, decolonial imagination. As the practice of loud-reading grew, the lectores (Loudreaders) will become traveling performers with an international audience, creating new networks of solidarity all around the Caribbean as well as a massive, shared, and open access oral library to workers who were denied any other form of formal education. The tobacco workers turned the mind-numbing characteristics of their repetitive, manual, and boring work of rolling cigars into an advantage, using the same space and tools of their capitalist exploitation to create an anti-capitalist underground culture.

Luisa Capetillo: LOUDREADER

Luisa Capetillo (b. 1879, Arecibo) was a worker, writer, labor organizer, and Loudreader. In a time when Loudreading was mostly performed by men, Capetillo—who had been arrested in La Habana for wearing a shirt, tie, pants, and short brim hat—offers a model for contemporary forms of Loudreading. In Puerto Rico, Tampa, and New York, Capetillo will Loudread texts by Kropotkin, Bakunin, Malatesta, while serving as a syndicalist representative for the workers and creating and distributing emancipatory propaganda.

In 1909 she publishes La Mujer (Women), and the following year publishes La Humanidad en el futuro (Humanity in the Future), a utopian tale centered around a central strike. She writes about freedom, sexual education, and the rights of men and women.

Notes Araceli Tinajero, El lector de tabaquería: historia de una tradición cubana , (Madrid: Editorial Verbum, 2007).

Luis Othoniel Rosa, The Tobacco Intergalactic School (Postnovis Branch in the Americas)’ Feb. 1st, 2019 – Feb. 1st, 2031

Luisa Capetillo (b. 1879, Arecibo) was a worker, writer, labor organizer, and Loudreader. In a time when Loudreading was mostly performed by men, Capetillo—who had been arrested in La Habana for wearing a shirt, tie, pants, and short brim hat—offers a model for contemporary forms of Loudreading. In Puerto Rico, Tampa, and New York, Capetillo will Loudread texts by Kropotkin, Bakunin, Malatesta, while serving as a syndicalist representative for the workers and creating and distributing emancipatory propaganda.

In 1909 she publishes La Mujer (Women), and the following year publishes La Humanidad en el futuro (Humanity in the Future), a utopian tale centered around a central strike. She writes about freedom, sexual education, and the rights of men and women.

Notes Araceli Tinajero, El lector de tabaquería: historia de una tradición cubana , (Madrid: Editorial Verbum, 2007).

Luis Othoniel Rosa, The Tobacco Intergalactic School (Postnovis Branch in the Americas)’ Feb. 1st, 2019 – Feb. 1st, 2031

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

LOUDREADERS