Palestine:

Reimagining

Solidarity –

a Conference

of Butterflies

Solidarity – a Conference

of Butterflies

The First Movement

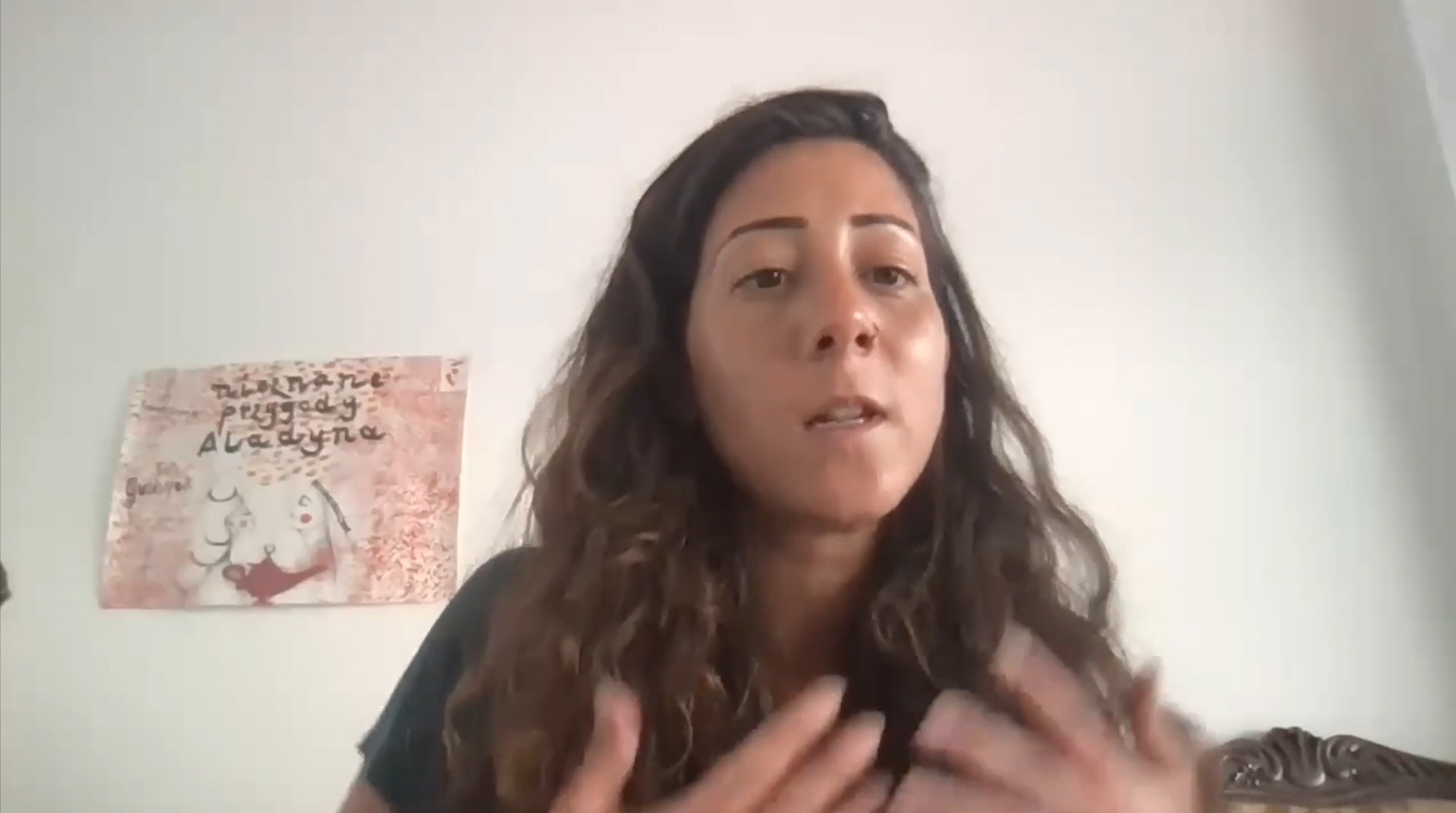

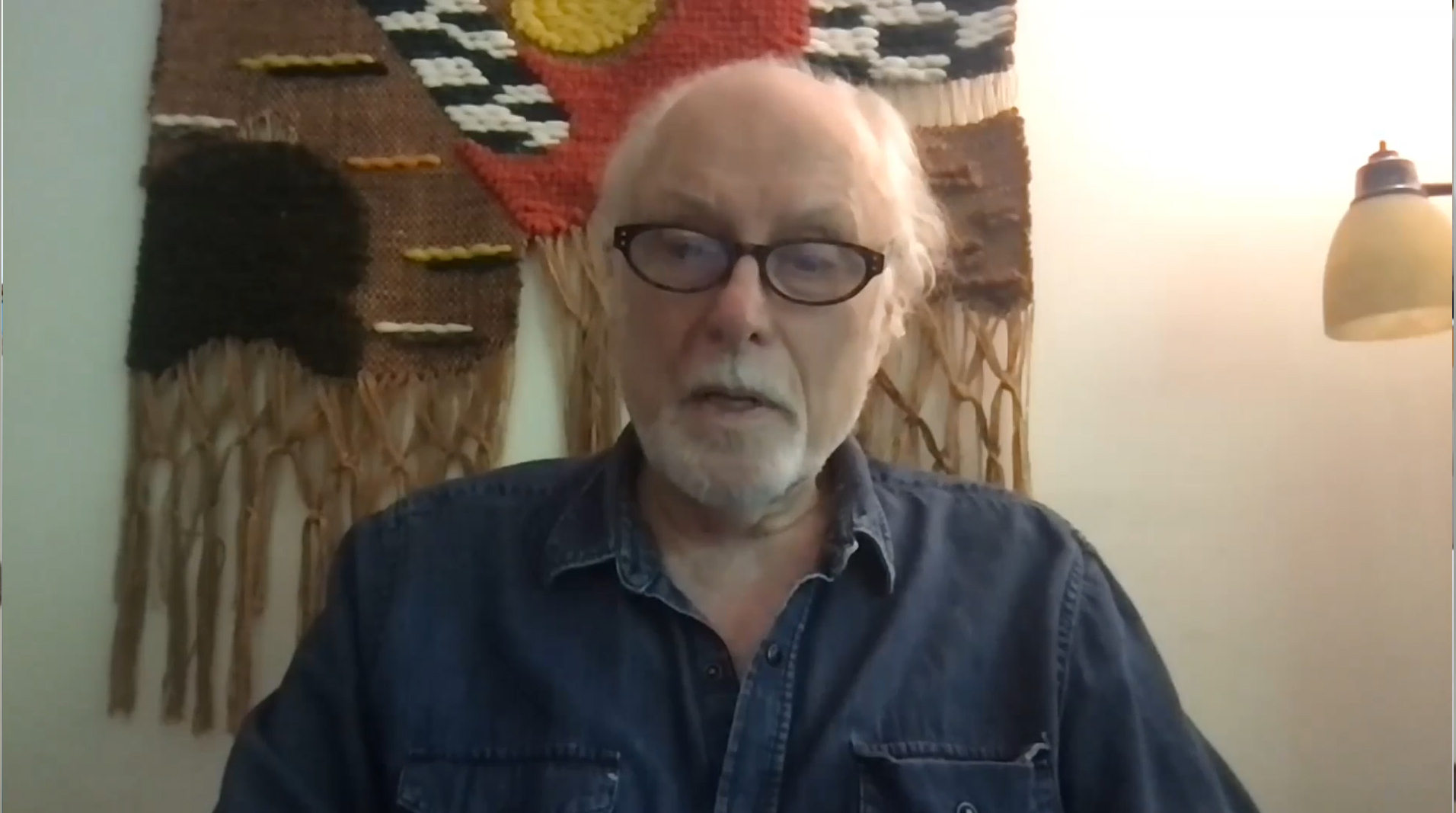

Reem Shadid, Ayreen Anastas, Munir Fasheh, Rolando Vazquez, Walter Mignolo, Valiana Aguilar, and Mahmoud Al-Shaer

Reem Shadid: Thank you everyone for joining today. I thought I would say a couple of words of how this came about. We started speaking about a version of this almost a year ago now, and for various reasons we kept pushing it or it changed in form. It started with thinking about “Exit Plans” thinking through, in relation to, and with Palestine. From that we started a Palestine study group with friends who are with us today and who helped to organize this conference. So we’ve been thinking about this for some time, but with the current circumstances, we felt it was an important time to organize a version of it. We will have five movements, each movement is about an hour long, where we have different speakers joining with 15-minute-long contributions, followed by some discussion and potentially other interventions by people present here.

As a way to introduce the first hour – I was visiting my mother for Eid, and I found in my late father’s library a book by Dr Sleman Bashir who was a Palestinian historian and sociologist and passed away in 1991. He wrote a book in the late 70s/early 80s, called “جذور الوصاية الأردنية: دراسة في الأرشيف الصهيوني ” “Roots of the Jordanian Protectorate: A Study in the Documents of the Zionist Archives”. I just started it so I can’t tell you too much about it, but what struck me was, which relates to what we’re doing today, and especially with the first movement, that he mentions in a couple of occasions the frustration he faces as a Palestinian historian in the academic and communist movement. How frustrating it is to constantly try to do this kind of work while everything is still happening in the present. The struggle for Palestinian liberation in Palestine, as Munir [Fasheh] was saying earlier, has been ongoing for 80 years. It’s not something that has passed that we can now start historicizing and thinking back about. It is happening in the present, and I find that, on a very personal level, something that I struggle with, how to process what’s happening in the present and my thinking but also how to grasp what specific moments are able to give us in terms of opening up possibilities. One other thing I’ve been thinking about in relation to the most recent attacks, and by the occupation in Palestine: I noticed there is a change in language, which indicates a change in understanding and perception, not only by people who are friends or are in our circles, but also on a more popular basis it is being contextualized as a struggle against settler colonialism. Even my mother now uses the English term “settler colonial.” In Arabic this is not new to us, we always use الاستعمار (Al Isti’mar), but in English, it’s new to be able to contextualize it like this. I see in the new generation the ability to open up and also learn from other decolonial struggles and other decolonial histories.

And of course, I still have many questions about it so I’m hoping this first hour is going to help me think through this. This movement will be rooted in decoloniality and reimagining what decoloniality means as we think about parallel struggles. It includes Ayreen Anastas, Munir Fasheh, Rolando Vazques, Walter Mignolo, Valiana Aguilar, and an intervention by Mahmoud Al-Shaer.

Ayreen Anastas: Thank you Reem. I will keep my contribution short in the form of a note close to a series of questions, which we asked with the Communist Museum a couple of years ago. Which concerns the relation and/or the intersection of three circles; the Palestinian struggle, the question of solidarity and the notion of communism, and the attempt to redefine the outlines of these three circles for us today. Where is the Palestinian struggle today, what forms of solidarity are most useful for that struggle, and whether a rethinking of communism may help us find and enhance those forms of solidarity?

One of the biggest challenges facing struggles today, and Palestine is not an exception, is the large waves of cooperation, capture and normalization by the bigger ensembles, the states, empires and corporations, while solidarity as we understand it, is enacted from the ground up, and takes risk by enacting itself. And communism as well, as we understand it, is horizontal, not hierarchical nor centralized. And in this light, I would like to ask, ”is there solidarity without communism?

It is a very interesting question because when I come to the word solidarity, I have to come to the Arabic word تضامن (taḍāmun) and open it and see how it moves in relation to the Latin derived– solidarityseems to be dense, solid, whole, entire, firm, undivided. For the sake of time, I will be brief, but I can say that a first notable difference in Arabic is that it is not only a state of being, but can be a verb. It is less about solidity and intimates toward securing, guaranteeing. If we had more time, it would be nice to stay there longer, but maybe to ask the question “is there solidarity without communism?” returns to the question “what communism?” I am thinking about this with Maria Lugones, and questioning what is white feminism vs. other feminisms? Is there something we can think of as “white communism” vs other communisms? This opens up a very big history of the left, and the notions or practices of solidarity. But maybe it is enough to interrogate the notion of communism and consider other kinds of communism to reimagine solidarity. Maybe it’s not a constituted communism, maybe it’s not state communism, it’s not an imposed communism. It’s another form of communism that one is searching for, even recovering, without which there is no solidarity. Because even the word solidarity in Arabic تضامن (taḍāmun) , includes a relationality within the word (تضامن على وزن تفاعل ).

تضامن (taḍāmun) in the poetic meter of تفاعل (tafa’ul) implies an interaction, an in between-ness and a relation. The literal meaning of تفاعل (tafa’ul) is to undergo some change or transformation by coming into contact with something.

So, in addition to being an action, it can be an interaction. One can emphasize this relationality and in between-ness, as opposed to ضمن (ḍamina) which means to guarantee and to make sure that something would happen in the sense of containing, “securing.” ضمن (ḍamina) falls in the poetic meter of فعل (fa’ala) which implies acting and doing. In this sense, تضامن (taḍāmun) changes the action of ضمن (ḍamina) into an inter-action.

تضامن (taḍāmun) would be less in proximity to the notion of containing or securing, but rather oriented by a relational notion of care. So, in a way, the notion of solidarity through Arabic can be brought out of containment and security and dissolved from its solidity into a question of relation(s).

Rene Gabri: I would add one quick note to whatever we have been thinking with friends around the Communist Museum of Palestine. It’s the idea of an everyday communism as an everyday practice. It is an ethic thatt we’re focused on, which our friend David Graeber quoting Marx used to say operates on the principle:”from each according to their abilities to each according to their need.” It would be an ethic, a sphere of relations where counting doesn’t make sense, where one is doing without accounting. If there is a decolonial communism it’s coming from that practice and ethic, not from a system or state formation. So how do we reimagine and reclaim it as an everyday practice and form of relating?

Ayreen Anastas: In this way, communism within the matrix of solidarity is also important because it allows and creates more interesting relations. By enacting solidarity with the other, I am also transformed changed and the notion of solidarity is less mono directional, for instance from an outside towards an inside of a place or a situation. And maybe I could conclude by asking another question more about the basis of that solidarity as well as communism. How to have a communism without universality, without universalization? It sounds like a paradox, but how to go beyond an image of solidarity or communism for that matter that affirms the shared, the common premises of life, in difference and multiplicity. I would like to conclude here and open the space for Munir’s reimagining of solidarity.

Munir Fasheh: First, I would like to say that in my 80 years of living, I went through the whole spectrum of the Palestinian situation. I was born in 1941, and when I was 4 and 5 years old in lower Jerusalem, there was a settlement next to us called “Mekor Haim” and every now and then they kept either shooting or bombarding or whatever, and often my parents would put us under their door frame because they thought this was the safest place. We did not have any shelters (I mean Arabs didn’t have shelters) because they never needed shelters until the British came. Then in 1948, I was one of the first refugees in the region. The refugee phenomenon started with me and my generation in Palestine. Then, we went from that to a series of events. After 1948, we had 1956 (The Suez Canal) and the attacks by three countries on Egypt. Then ‘67, ‘73, ‘82, ‘87, then ‘93, then 2001, then ... and so on.

But I would say very strongly, although I lived in the First Intifada as very hopeful, and I lived in 1956, also hopeful. But there was nothing in the past 80 years that comes close to what happened in Gaza last week. For me, if I want to summarize what happened, in my feeling, it was the death of nationalism, and the reawakening of a civilization horizon. Now we are living in a civilization horizon. We are not living in a state. We are not living in small artificial enclaves, whether we call them empires or states or whatever. We are living within a civilization horizon, and I think this is very important. Because it makes all the other words like nationalism, colonialism, all these words like left and right and national, religious or whatever– all of these are gone.

They do not come from real soil. What is different, I think, between Gaza and Israel, is this: the people in Gaza are connected to different soils that are real, starting with the soil of the earth, and then the soil of the community the communal soil. And then, the soil of the cultural, the knowledge soil. Then there is the soil of affection. Their hearts are together. They are not just part of a party, the way they behaved and did things and expressed things, they belong to a whole civilization that has been in place for a very long time until the British and the French came, then later the Americans and Israelis. So, I think this is a very important thing to see. We are much wider. And it came from the smallest, weakest spot in the region: Gaza. This also reminds us that all the words we have to have– a big empire, a big this or that, universities, degrees, experts, doctorates, all of this is nonsense. The people in Gaza right now are reminding us that all the things we believed in were very shallow. They connected us back with a civilization horizon that is comprised mainly of Arab countries and countries around us like Turkey and Iran, and Pakistan, and from all over the world, places where people really were part, or became part, of this horizon. So, our horizon now really encompasses the whole world.

And to me this is not a marginal thing. We don’t even need words like solidarity, because what we are experiencing is something more. Maybe we can sometimes perform solidarity, but it doesn’t have this spirit which really goes around the earth. It is a very amazing feeling. I can’t tell you how different it has been, from anything that I have lived before, which was wonderful, but I never lived a moment like this one.

It definitely broke through all the things that surround me, whether in terms of my mind, my body, my heart, my thinking, my sense of belonging, all of it. That’s why I don’t even want to use the word colonial, for the simple reason that it is not my reference. Our civilization horizon is my reference now, and I want really to stay with that. And I want to remind young people, especially in the region that I’m in, in Palestine, Jordan, the Levant, Syria, Lebanon as one body that I lived and loved, to include all the neighboring countries in Africa, in Europe, in Asia, in the Americas.

Especially, I would say, the closest I always feel is to the Zapatistas. Because they have waited and endured for 500 years until they came out after five centuries with something so hopeful, so simple, so energetic, so alive, so powerful, and I felt when I visited Southern Mexico: wow, if these people did not stop feeling the soil they came from, especially their civilization and culture, why should we as Palestinians, told after 70 years or less actually, to forget about most of Palestine? Because the Oslo people really wanted us to forget. So, I think that these events really open up our minds.

And in order to wake up our minds we have to change our language, because they defeated us from within through language. A language that is made of statues and not of something that is alive.

There is a sentence by Shams Tabreezi, I will try to translate it. He said “I told him my heart is made of mud; he said his heart is made of iron.” Shams continued “I told

him with the first rain the mud will become flowers, and your iron will become rust.” “I will flower and you will rust.” And I think this is exactly where the Gazans have flowered. Because their house is made of mud - not of strong organizations, not of governments, not of international garbage, not of any of these things. So, with the first rain they flowered. And the rest that were opposing Gaza and Palestine rusted. Netanyahu is now full of rust, and the Gazans are full of flowers. So, I would say that I still feel there is a very weak point, not only in Palestine but in the world. This weak point came with the concept of education, and the father of modern education, Comenius, who was made invisible because he said something that explains the virus that has been in action for 400 years. He said, “people who learn without being taught are more like animals than men.” He killed learning as the deepest biological ability in human beings, like breathing.

I think what happened in Gaza in the past so many decades is this: they have been learning. But not learning through being taught– learning from life, from struggling to make sense, from struggling to stop the garbage, the injustice, the attacks, the killing and bombing, everything. And they learned, and they learned a lot. And what we see in Gaza is the concept of learning that has nothing to do with education. It has nothing to do with teaching, has nothing to do with professionals, with academicians, with experts, with institutions, with universities, with all of that. They have learned a lot. This is what I would say is the miracle that is called learning which has been suppressed by education, which has been suppressed in religion by again, institutionalizing it. To me, this is a time when we have to regain this bit of religion which made human beings in direct relation to god, which means there is no person who is less than another. We have to really regain everything that has been nurturing us and that has been corrupted by different means but mainly by institutionalizing life. I mean– if food is institutionalized, if breathing is institutionalized... But the worst thing is what happened to the mind: institutionalizing learning. It was not by chance, but by design. Comenius defined learning as the result of education, otherwise people are like animals. When he said that, he was invited by three countries that were forming a nation state (this is 400 years ago), and they were looking to control the people within the nation state. And the three countries were Britain, France and Sweden. And you know who else really wanted him so badly? Harvard University.

Harvard was looking at the time for its first university president. And they sent John Winthrop to Europe to meet Comenius and beg him to be the president of Harvard.

So why did everybody quickly love this man? Because he had a means to control people by denying their ability to learn without being taught.

So, all of these things in my opinion are lessons and show that it is our responsibility to help in this spirit that Gaza produced in the world. I personally cannot do what Gazans do, but I can do exactly the same parallel logic of getting the enemy that is in my head out of there. The enemy who wants to get in and defeat me from within. And they succeeded for many years, I was 26 years old in the war of ‘67. And in ‘67 was my first awakening that there is something wrong with education, with the knowledge that we have, because the war happened and it ended and we didn’t understand anything, we didn’t expect anything. We were like parrots, saying what we learned in universities and passing it to our children and so on.

So, 1967 was the first shakeup. It took me 4 years before I could translate that rebellion to action. And I started with some friends in 1971 with what we called the voluntary work movement. This spread in the West Bank and in Gaza. We started it in Ramallah and Al Bireh. For about ten years we did not have any internal laws, rules or bylaws, we didn’t have any money. We worked for 10 years with no categories, we were not categorizing things, there was no hierarchy, and there was no old person or young person. We were all equal, and it was an amazing ten years.

Rene Gabri: Maybe the biggest question today is how does solidarity transform into something like what you’re describing, which is an everyday form of action that is in resonance with this horizon you’re talking about. There is a lot to come back to, and we hope there will be more than this occasion.

Rolando Vazquez: I’m now a bit stuck in listening to Munir. So I want to start with the gratitude of listening to him as an elder, as a living voice and a living memory, and learning from him and his testimony. I think if something can move us beyond the notion of solidarity, is to witness and become witness, to learn each other in the way that, as Munir is saying, education doesn’t fulfill. So, in a way I prefer for him to continue speaking than me intervening, because it feels so important, what he is sharing as a living memory. And it is something that most of us really need at this moment. So I will be very brief with the hope that we will listen back to Munir.

Munir was referring to the Zapatista movement. Here for us, the idea that the Zapatista have always subscribed to this ethos in their struggle, that it is a struggle against oblivion. So forgetting is really what endangers and is the gravest danger to hope and the possibility of freedom, and the possibility of justice. And we can have the hope of freedom and justice because we don’t forget. It’s because we can fight oblivion. And here Munir is telling us that in order to remember, as two words, with a slash: re/member. So membering back what has been dismembered. And the way we have been dismembered precisely to forget this relation to soil, to the earth, to the communal and to our own ancestrality. In a way, modernity imposes a condition of amnesia, a condition of forgetting, it is an amnesiac situation on which power depends. So not forgetting is fundamental. And here, receiving the testimony of the elders is the most valuable seed in order to continue flourishing when the rain comes. I think we all learn from many struggles around the world that hope comes because there is a possibility from the flourishing of the seeds that remain. The seed is a living memory that cannot always be activated because of conditions of oppression, of coloniality, but it is always in reserve to transform the present.

So, this is part of my gratitude for listening to Munir as we have listened to him in previous occasions. Borrowing from this, I want to add a couple of things also in the hope that we can listen to him again. How can we go beyond the notion of solidarity, which is a question that Rene and Ayreen posed. How to move towards the relational and the coalitional? In a sense, the modern notion of solidarity doesn’t allow for those understandings of the coalitional and the relational.

Maria Lugones is one of our elders, who we remember dearly as she passed this past summer. She was a great thinker of coalition; coalition being thought through the thought of women of color. She shows us very clearly that coalition across systems of oppression is not the same as how we understand solidarity generally. For her, coalition implies an epistemic shift, and I would like to add also an aesthetic shift. Being in the binary of the relationship between oppressed and oppressor, we don’t see each other across oppressions, and in order to learn each other we need to go beyond the dominant framework of domination. In order to learn each other, we need to generate our own forms of listening to each other, of learning each other. Of becoming one another.

And this implies a transformation of the mind as Munir is saying, but also transformation of the heart. So maybe translating into more academic terms, it becomes an epistemic struggle and an aesthetic struggle. It requires that we stop thinking through the dominant categories. Resistance is often bound to those categories, just resisting them, and we can begin thinking beyond the aesthetic frameworks that are imposed on us, which define what is a good life, what is a good place, and so on. It implies that we recover the possibility of remembering who we are, in plural. Who we are as body-earth, as communal bodies, as relational beings. And opening in this way the possibility of learning from each other, which of course Maria is bringing from Black feminist thought.

So, in this way, I have always said that the decolonial aesthesis or decoloniality in general, is under the sign of the return. Because it is a movement of return that carries the possibility of justice and the possibility of hope. And in this aspect, it implies a different temporality than the temporality of modernity, which is so bound to futurity and the power of controlling reality, of controlling the life of others, of becoming an individual subject.

So I will close by saying that indeed we need to think solidarity in other terms. We need to think of solidarity in coalitional terms, in the way that Maria Lugones is thinking of coalition that implies an epistemic and aesthetic shift, that implies a turning of the mind and a turning of the heart in order to enter the possibility of relationality. Of relational forms of worlding the world, of learning from each other, and not just learning from the hegemonic system.

With this I will close and I hope we can give the word back to Munir before this first movement finishes. Thank you.

Walter Mignolo: I can give my time to Munir. I agree with Rolando that what Munir is sharing with us is crucial. I’m not trying to get off the hook, so I can say something in five minutes and then we can go back to Munir.

So, I will say something precisely to emphasize some of the points that Munir and Rolando have made. I will start with two things: I propose that communism and solidarity are no longer words or concepts that can help us, and I think the point Munir makes is that we need a new vocabulary, a new way of engaging in conversation.

In that sense I will say that the communal is for me and many other people a key word, and it’s very different from the communist and the common good. The communist and the common good are concepts that come from European Enlightenment, while communal is what we learn from memory and from people, like Palestinians, indigenous people, African, from traditional knowledge, but also captives in Haiti.

So, the communal needs coalition. Coalition to build something that is being destroyed. The common good and communist tried to build by obligation. I think that is Munir’s crucial point. Education is confused with schooling. Schooling is to make your mind captive and destitute the biological cognitive force of the human body. And I think Munir has been very eloquent about how the Palestinian people have been learning. So, the question now is what do we learn. We are not Palestinians; we are not in Gaza. So, what we have to do is to pay attention, to get out of the captive mind. Because the big changes in history are not the revolutions that are told in the history books. The great changes come from changes of emotion-ing. And to change the emotion-ing you have to change the way of knowing. To change the way of knowing, you need a different starting point that cannot be the system of education into which we are forced.

I think Munir was very eloquent on that too when he said that when he was 26 he began to realize that something was not quite right. I think to all of us here something very similar happened in our lives which made us change the way of our knowing, change the way of our learning, and change our way of emotion-ing. Because without emotion-ing we cannot change, we cannot change rationally. Rational choice, we know, was one of the most drastic ways of controlling people.

And I will make one more final point. Munir mentioned the Zapatistas and Rolando followed up. We are learning with Rolando from our friend and colleague Jean Kasimir, that the Haitian revolution was not the creation of the state, Toussaint Louverture, Dessalines, or Christophe. Yes, they were important in cutting ties with France, but the nation, they failed. And the nation was built by the captive, not “the slave”– because the slave is the vocabulary of the French. Captive is the term that is introduced by Kashmir as somebody who comes from that memory. Captives built the nation through the 19th century that remains until today. They came from different parts of West Africa, some from Central Africa, they have different languages and belief systems. They were free, and you cannot forget when you are free. That is what they have in common, the 400,000 captives and the few enslaved from the the previous generation have that memory. And that memory of something that happened in the process of 14 years of uprisings, from 1791 to 1804, which allowed them to build themselves, build something absolutely new based on their memory, but also build in coalition, build the communal and build the nation of Haiti that is not the state of Haiti. Munir’s description and the history that he told us, reminds me of this. I don’t know much about Rojava, but maybe that is another case in which a kind of delinking from the state, the corporation and from what the international funds and banks want us to do become necessary in order to save our lives. So, thank you Munir, keep on telling us your story.

Valiana Aguilar: Gracias, thank you Munir also for sharing with us, it’s good to see here many friends. I just want to share that also with CCRA (center for convivial research and autonomy) we have been thinking about this war on communities, collectives, women, and when we are trying to imagine this war, we always come back to the Zapatistas. We say this struggle is against oblivion. I could share a little bit about what we have been doing here in the Mayan community, which is a mirror of many other indigenous communities in Mexico.

A couple of weeks ago we had a meeting with the Zapatistas. They arrived to Yucatan because the boat (to Europe) was going out from here, and the first thing they said to us is: “what are you doing in terms of autonomy? we don’t want to hear what you are suffering because we already know, because we are suffering the same dispossessions, violence, deaths. We know what is coming with this Mayan train, that the mega-project wants to erase the Mayan community here. And we’re fighting against this, with our bodies, with our communities.” And we tell them: “the only thing that can help us survive as Mayan communities is coming back to our asambleas, to the communal. This is our last battle; this mega project of the Mayan train wants to erase us. We cannot imagine the impact of that in our communities.” And the Zapatistas respond: “the only way to survive is coming back to the communal, to the asambleas, to the fiesta, to be a collective again. That’s the only way of surviving. And coming back to autonomy, the autonomy in every area of our lives.” We say that we refuse the epistemicide that exists in our communities. We refuse it and come back to the ways of how we live, how we eat, how we heal, how we learn collectively, and that’s how we go back to our autonomy and resist all these mega-projects in our territories.

In coming back to these communal ways of living, we are resisting and we are refusing to forget. The way that we plant our milpa, coming back to milpa, is a way of resisting this capitalist system. The way that we construct our houses as our grandparents, our grandmothers used to build 3000 years ago, is a way of refusing to forget who we are. We are also trying to exchange our seeds for example, our ancestral seeds, that have memories of 10,000 years, and that’s a way of refusing to forget who we are. And sometimes it’s hard, because this war as Munir says, has been waged against us for 500 years.

We know that it’s hard to fight this system, but we also know that this long night of 500 years, was a night where our grandparents used to pass their learnings and their knowledge in the dark. There are some things they don’t show, because if they show their organization, then the companies, the government, the system would kill it immediately. But we know how to keep this knowledge, this learning in communal ways, in our practices in the night. We say, that’s the way that we walk. We don’t show to everyone our communal practices. But now, we know that in this war, in this new context that we are living, in which they want to erase us as communities, these tools, these communal tools, we need to share them, we need to learn, we need to listen, we need to weave collectively another way of solidarity. Maybe it’s beyond solidarity, maybe it’s a way to share our practices of resistance, and share those seeds in order to resist this system that’s killing us.

Thank you for saying all these things, Munir, because we always connect the struggle of Palestinians here also, and sometimes we translate your text about mathematics. We always come back to this point: how we could build our houses with our embodied knowledge. It’s pure mathematics, if you want to say it, but we don’t call it that. So, thank you, we always go back to that.

Munir Fasheh: Thank you very much. I know I don’t have a lot of time so I want to be very concise. I want to go to the question that Rene asked. What do we do? I would put forward a word to combine the words by Rolando, Walter, and Valiana. That word is soil. There is no nurturing without soil, whether we’re talking about land soil, or communal/community soil, cultural soil, civilization soil, or heart soil. I think that soil is very important.

So, what we can do, to really be inspired by what happened in Gaza, is exactly what Gazans are powerful at: using every soil that they were living, that they could be nurtured by, in particular, the communal and cultural, civilizational soil. This is their power. Without these soils they would not have been able to do what they do. They would have repeated things that would have no soul– soil and soul are very crucial. So, what I would say, let’s again, as individuals and as communities, and as small groups, connect to the soil around us.

I cannot connect with the soil in Gaza, I cannot connect with the soil in Rajastan, with the soil of the Zapatistas, but I have my own soils. If I connect to my soils and be nurtured by them and nurture them, and if we all do that, I think this will be a very powerful momentum that will defeat, maybe not nuclear bombs, but will defeat all those who are working for capital, to make more capital, more for themselves, or for their countries or for other motives. So, let’s connect back to soil.

I spoke about the communal soil starting with my family and the neighborhood, then with people in the West Bank after 1967, and then in the 80s and 90s until now. And it’s very sad, the only time we lost these soils was when we had the Palestinian Authority. Because actually it was not a Palestinian Authority, it was the World Bank that had the authority. And we became enslaved to the World Bank. Gaza was safe because there was no World Bank there. No bank really stepped in there in the same way they stepped in Ramallah.

So, let’s go back to soils and be nurtured by all the soils that give us life, give us aliveness, give us understanding, give us knowledge of a different kind. And at the same time, nurture them, so we do not consume them. We live them, we are inspired by them, we are nurtured by them, but we have to nurture them. We nurture them by our stories, by whatever we go through. And I think right now, Gaza is full of stories. It is full of what can nurture the soils that nurtured them.

I will stop here because I think the time is up.

Reem Shadid: We would love to hear more. We are a little behind on time, but does anybody have a question?

Rene Gabri: I saw Mahmoud Al-Shaer is joining us from Gaza. So maybe, Mahmoud, you wanted to say something?

Mahmoud Al-Shaer: Hi everyone. Maybe Reem you can help translate?

Reem Shadid: I will try to translate. Mahmoud is saying thank you Munir and everyone, he was particularly inspired by the way that the investment to redevelop or keep existing was seen, which is based on building on what has been broken, what has been demolished, and our way of basically learning from life, how to continue living in this life in this very precarious situation where everything can fall apart in any moment.

The occupation infiltrated all aspects of life, so even while speaking right now, we might be disconnected from power or internet. But, also, the loss of everything has given us an opportunity to experiment on how to resist and fight the occupation, how to keep on living.

I had a question for Munir. How do we continue fighting this fight despite everything?

Munir Fasheh: If we really think of those who have been in jail for 20, 30, 35 years, and you read some of their writing, it’s amazing how they’re full of hope and energy, more than people outside. People are a miracle. Of course modernity tells us we cannot survive, we cannot do anything by ourselves and we have to depend on experts and academics, but this is not true. This is what Gaza has proven. It is the smallest weakest point on earth and to me it has revived a lot of what has been made impossible, of what we thought was impossible. For people who feel low or no hope, who saw what happens in Gaza with so little, while surrounded by enemies, this is exactly where hope is.

If I want to say something about what Ivan Illich said, and I think it is one of the most beautiful things he said: modern man is the one who stopped living with hope and became a servant and enslaved to living with expectations. We who are outside Gaza, like in the West Bank, Lebanon, or many other places, we thought we were feeling hopeless because we are living with expectations. Gazans are not living with expectations, they live through their inner soul as individuals and in community. What happened is a miracle– the Iliads and all these epics are nothing compared to Gaza. How can we build on that, first to change our superstitions because modernity is full of superstitions. Gaza to me is an amazing miracle that will last for as long as humanity lasts. That’s how I feel. I’m not saying this just to say something good, but I’m saying as I’ve lived the whole recent experience of the Palestinian situation, but I never felt as energized, as alive, as hopeful. Not hopeful in the sense of we are going to get exactly what we want, that’s not hope. Hopeful is to do what needs to be done without asking what is expected. Just to do it. And i think this is the energy, Mahmoud, that Gaza gives us. Not only in Palestine, not only in the region, it gives this to the world.

Mahmoud Al-Shaer: Thank you everyone. Thank you for this. When we are under attack, your voices, all your voices, make us feel like we’re not alone, and that we fight for our lives, to save our people in Sheikh Jarrah in Jerusalem. All of your voices make us feel that every human in this world knows that we fight for our freedom. Thank you so much.

➔ Return to:

Capetillo: Journal for Crafting Futures

Reem Shahid, Ayreen Anastas, Munir Fasheh, Rolando Vazquez, Walter Mignolo, Valiana Aguilar, and Mahmoud Al-Shaer, “Palestine: Reimagining Solidarity - a Conference of Butterflies,” Capetillo: Revista para tallerear futuros No. 1, (2025), 28-33.

The following text emerges as the fruit of several collaborations. It is based on a transcript of the first movement from “Palestine: Reimagining Solidarity – a Conference of Butterflies.” The virtual conference was organized in May 2021 by Exit Plans, simultaneous to a mass Palestinian uprising, the Unity Intifada and a general strike across historic Palestine. In our words, “on the precipice between catastrophe and a planetary Intifada, we are reaching out to a community of thinkers both within and outside Palestine. [...] We are not searching for what is to be done, as much as what is to be asked? With whom? And which are the questions that may open further the paths of struggles and converging

of struggles?”

Exit Plans has been initiated in 2020 as a study group/field after a call by the Communist Museum of Palestine inviting cultural practitioners during the pandemic to consider how we may exit from reproducing the social and cultural infrastructures maintaining racial and class supremacy by policing and determining whether, when, how and which lives, cultures and histories matter. In publishing this text in 2025, witnessing the countless forms of repression exacted by cultural institutions against artists, faculty and students resisting genocide, this question remains a central one. The conference has been organized in collaboration with two spaces of communal un/learning 16 Beaver Group and Testing Assembling.

The editors of this issue of Capetillo have worked together with us to publish a conversation which we believe only grows more relevant in the midst of a renewed genocidal campaign against Palestinians. We understand the current wave of atrocities and destruction of life worlds perpetrated by the Israeli military/settler complex as a more intensified moment of a much longer history of colonial crimes. And as our contributors here remind us, it is also a long history of struggles resisting such brutalities, showing us the means for outliving the genocidal denialist futurities such violence seeks to impose.

Repeating the question alluded to above, we can ask: How do we renew our efforts on a planetary scale to abolish, decolonize, communize and/or exit from reproducing the institutions and infrastructures which have condoned, denied, justified, rationalized, sanitized, unseen, prolonged this genocidal violence not only being perpetrated against Palestinians, but also against

all the indigenous, abducted, displaced and colonized

peoples of earth?

We are grateful to the editors of this issue of Capetillo for providing a space for this text to circulate further. We also thank all our contributors, the writer Mahmoud Al Shaer and the artists in Gaza who continue to give voice to and affirm the life which is today under attack and erasure.

https://16beavergroup.org/palestine/